During a recent explosion investigation, this author discovered a new failure mode that is not sufficiently addressed in NFPA’s trio of industrial heating equipment standards (NFPA 85, NFPA 86, and NFPA 87) that cover Boilers, Ovens, and Fluid Heaters, respectively. The failure mode occurs only in heating systems equipped with natural gas burners and flue gas recirculation (FGR) for control of NOx emissions. The investigation where the failure mode manifested itself happened to be concerned with a boiler explosion, but ovens, furnaces, and fluid heaters are equally capable of experiencing the same problem, if certain factors are in play.

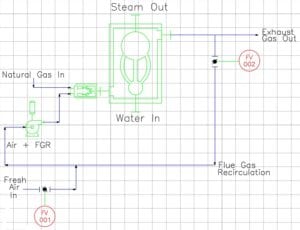

The schematic below identifies the primary equipment that plays a role in the incident scenario. In addition to the boiler, burner, blower and natural gas source, there are two flow valves (FV-001 and FV-002) that control the amount of FGR blended with fresh air that enters the burner. On smaller boilers, FV-001 is set manually during commissioning to approximately 50% open and rarely changed, whereas FV-002 is typically an automatic valve with two discrete positions – closed (no recirculation) and normal (standard recirculation).

NFPA burner safety requirements require a pre-ignition purge at the beginning of each burner startup to help ensure the combustion chamber is free of residual fuel gas or any other combustible vapor. NFPA burner standards have included a purge requirement for at least 50 years and such requirements have reduced the rate of explosions significantly.

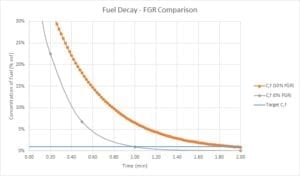

The goal of the purge cycle is for approximately 4 volumes of fresh air to be admitted into the combustion chamber to drive out any unwanted combustible gas or vapor. For example, if the combustion chamber has a volume (𝑉 = 100 ft3) and the blower is delivering a flow rate Vdot = 400 acfm the purge time should be 𝑡 =1.0 min. This amount of purge is almost always conservative enough to ensure combustible vapors are diluted to a nonflammable concentration in the firebox. The very first volume of fresh air purge in theory is enough to remove the combustible vapors if a plug flow model is assumed for the air flow inside the chamber. The requirement for 4 purge volumes arises from the fact that the plug flow model isn’t conservative enough if plug flow behavior is not achieved. Hence, a perfectly-stirred vessel model is used instead. The decay of fuel concentration in the firebox is exponential with time, and 4 volumes of purge air will take a 50% fuel concentration down to 1%.

However, if the purge air isn’t comprised of pure air, but rather a mixture of “flue” gas with a high concentration of unburned fuel from the prior unsuccessful burner ignition attempt, the purging process is much slower. The figure below shows the difference in decay rates between the normal case, where the purge air is 100% air, and the compromised case, where the purge air comprises 50% FGR (with residual fuel) and 50% fresh air. When purge is carried out with contaminated air, the number of purge volumes required is 8, not 4.

For the boiler explosion case described above, this author found that FV02 had been unplugged from its power source and the damper was stuck in a partially open condition. After 3 unsuccessful ignition trials in rapid succession, the spark igniter set off an internal deflagration that damaged the vessel walls such that a complete replacement of the boiler was required.